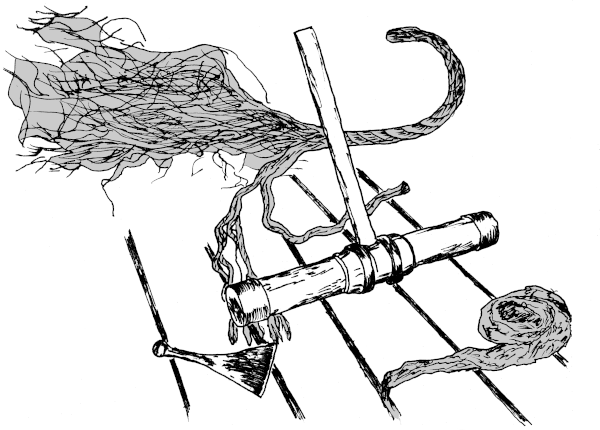

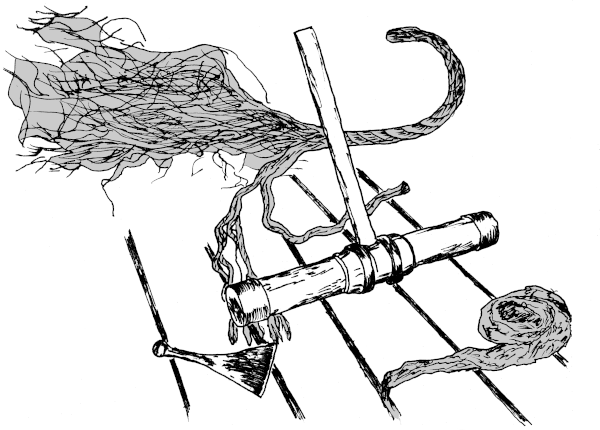

Figure 10.1: Rope Picked Apart for Oakum, with a Caulking Hammer and Iron.

| Chapter 9 | Introduction | Chapter 11 |

Figure 10.1: Rope Picked Apart for Oakum, with a Caulking Hammer and Iron.

Picking oakum was something sailors did in their spare time on ship.[215] It was also a task assigned to prisoners, orphans, and the poor. Picking one pound of oakum a day was for young girls and the seriously infirm.[418] Hardened prisoners were given up to six pounds of oakum to pick per day as punishment. Picking oakum is rope making in reverse.

This is a good use for small pieces of stuff lying around your shop that aren't picked apart for oakum.

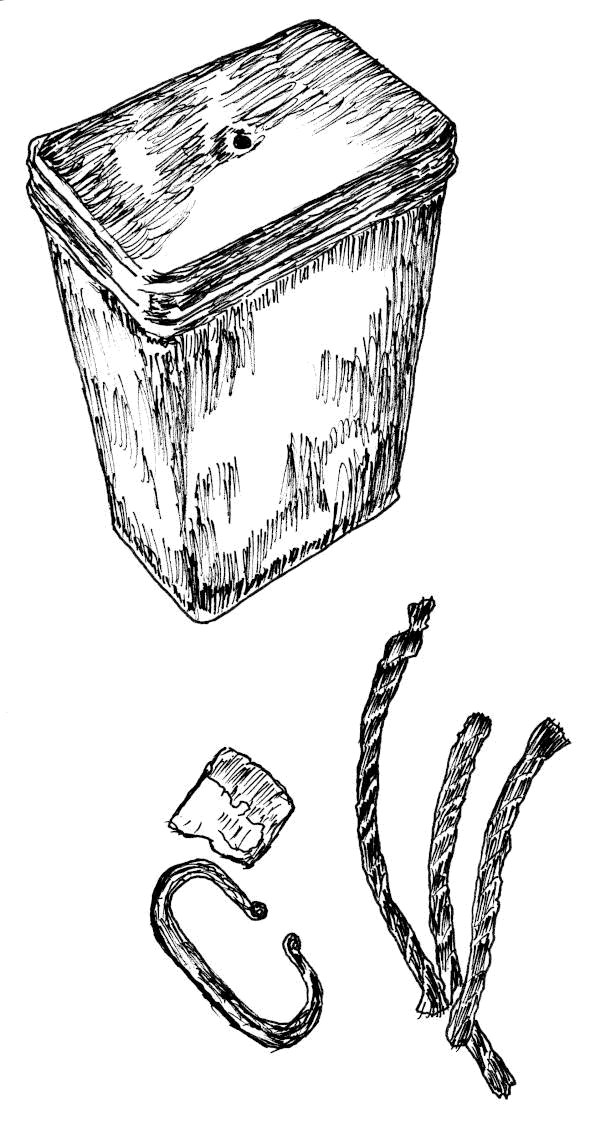

Figure 10.2: Clockwise from top: Tin Can for Making Charcord, Three Strands of Charcord,

Striking Steel, Flint.

Figure 10.2 is a tin can about eight inches tall, with a tight fitting lid. The lid needs a hole to let gasses escape, and you need some way to easily seal the hole. I just whittle a stick to fit the hole. If your plug stick is long enough, it can help you move the can out of the fire when the time comes.

To make charcord, put pieces of natural vegetable fiber ropes in the metal can. Don't pack the can tightly, the tars and gasses need to space to move, or else your charcord will be a tarry wad of fibers.

I put small branches in with the rope scraps. This keeps me from over stuffing, and makes channels for the fumes to travel. Sometimes these are pencil diameter branches I've previously peeled for bark. Sometimes, it's just dry sticks from the garden.

Make sure gasses can flow through the hole, then put the can full of cords in a fire. After a while, steam and smoke will jet out of the hole. These gasses are flammable, so you can light the jet for the amusement of any watchers. After the gases have stopped coming out of the hole, block the hole with a piece of stick, or what have you, and take the can out of the fire. Blocking the hole keeps oxygen from contacting the hot charred rope inside. Combustion requires three things: fuel, heat, and oxygen. If oxygen gets into the can while the charcord is still hot, you will end up with a can full of ashes. If the cooked cord cools without oxygen, then you get the desired charcord.

If you've put sticks in the can with the rope scraps, those twigs will now be charcoal also. Artists like real charcoal sticks for sketching. And charcoal is great for making a temporary sign board, or illustrating a point on your table-top. Nowhere near as messy as ink, and it wipes off. Somewhat. These are the byproduct of a byproduct.

Finer fibers, like cotton, hemp, or jute will catch sparks better than coarse fibers like modern manila, or sisal.

| Chapter 9 | Introduction | Chapter 11 |

| Colophon | Contacts |